January 2008 issue

EVE

by Anouar Benmalek

When she heard that her older son had murdered her younger son out of jealousy, in a murky quarrel over a present offered to God, Eve froze in place, stupefied, incredulous. It couldn’t be. She knew that she and Adam were at the beginning of a great adventure. She didn’t know yet exactly what sort of adventure, but she was sure it would defy the imagination, even God’s imagination, the thought came to her, the day she gave birth to her first son, biting her lips with fear and pride. In fact, that was one of the first secrets she stole from the fount of knowledge: something like Humanity was going to exist and would endure for as long as sun and water and the rich earth all about them endured. It simply was not possible for God to bungle his own work so quickly.

But Adam shed such bitter tears, she realized the impossible must have come to pass, because the only time she’d ever seen him weep that way before was on the day the Eternal drove them out of Eden. With good swift kicks, sagging like donkeys under their burden of shame. . . .

She stared at the meal she had been preparing: the toil of her son the plowman furnished the bread and vegetables; the lamb stew came from the sheep her son, the herdsman, had slaughtered the night before. A dry sob rose in her throat. She groaned and knocked the clay pot to the ground.

“Where are they?” she shouted and rushed outside, without waiting for Adam’s reply. She caught sight of her older boy running toward the east but was too short of breath to yell after her beloved son, the unlikely murderer. She tumbled panting down the hillside dotted with bright poppies, and nearly tripped over the body of Abel, her other beloved son, the murder victim.

Unlike Adam, Eve had never actually wept when they were expelled from paradise. She had been rather relieved, even if the grounds cited for their eviction were totally incomprehensible to her. In the garden, they were under constant surveillance; the smallest stones, the drabbest wildflowers were so many spies in the service of the Lord of Creation and his strange whim: the ban on touching the fruit of the thousands of apple trees planted all over the garden of Eden, in its rich soil. At least if those apples hadn’t been such an ordinary fruit, if, for example, they had been those delicious translucent dates, as sweet as her husband’s kiss . . .

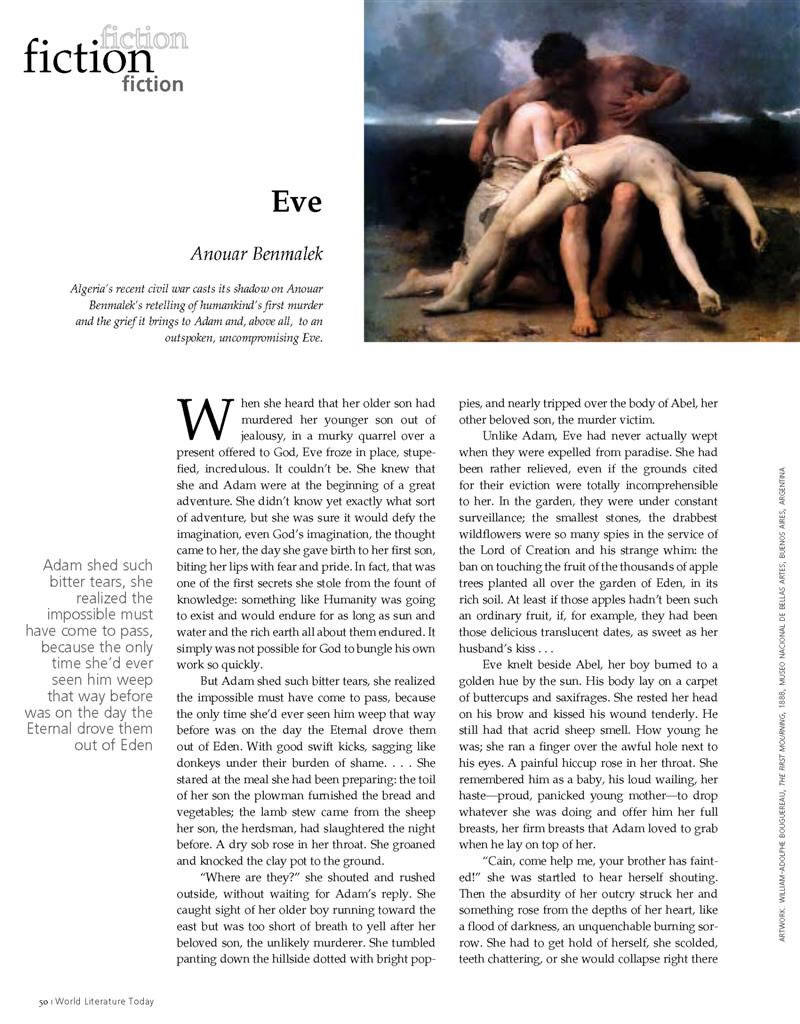

Eve knelt beside Abel, her boy burned to a golden hue by the sun. His body lay on a carpet of buttercups and saxifrages. She rested her head on his brow and kissed his wound tenderly. He still had that acrid sheep smell. How young he was; she ran a finger over the awful hole next to his eyes. A painful hiccup rose in her throat. She remembered him as a baby, his loud wailing, her haste—proud, panicked young mother—to drop whatever she was doing and offer him her full breasts, her firm breasts that Adam loved to grab when he lay on top of her.

“Cain, come help me, your brother has fainted!” she was startled to hear herself shouting. Then the absurdity of her outcry struck her and something rose from the depths of her heart, like a flood of darkness, an unquenchable burning sorrow. She had to get hold of herself, she scolded, teeth chattering, or she would collapse right there on the spot, incapable of taking action. But just what should she be doing? This was the first time a human being had died, and no one knew what gestures were supposed to accompany death. She had faced the loss of life before, of course, with Abel’s sheep and goats, or the deer her husband, a skilled marksman, sometimes brought home. Those deaths brought pleasure. Even at that moment Eve recalled the years when the pleasure was new. They had left Eden, the children had already been born, Adam went hunting all day and often met with luck.

“The Eternal gave me the gift of unerring strength,” he used to boast. After they ate the roasted game, she and Adam would put the two sleeping children to bed. The man and the woman would gaze at each other, smile at each other, and grow wild with excitement over the approaching encounter. Melting witdesire, Eve would stretch out on their bed, brimming with the happiness of a mother and lover. Adam would bend over her and undress her and caress her slowly, till he reached the magical cleft. Abel’s body lay motionless. Eve murmured, “Am I to eat you then, my son? Till now we always ate the dead.” A grasshopper hopped onto her son’s bare breast, Eve brushed it away distractedly. The ground was muddy. She had dirtied her hands and knees. A fox and an ermine slunk near the corpse. The ermine sniffed alertly at the puddle of blood. Eve picked up a stone and threw it with an angry grunt and hit one of the critters, to judge by its shrill cries.

Adam had caught up with Eve, but hung back, arms dangling, dazed with grief.

“….Damn you, Cain. Why did you kill your brother? You used to protect him when you were little. You didn’t like me scolding him, when he broke something. Sometimes you even took the blame for him!” Still kneeling, Eve gazed after her fleeing son. The valley was beautiful, home to so many animals and plants she knew only a tiny fraction of their names. Adam, when she inquired, always postponed the task of naming them. The haggard mother wondered aloud, “My little one, your brother’s murderer, how will you survive? You will be cold and hungry where you are going. Wild beasts will want to devour you and I will not be able to protect you. And your younger brother, the murder victim, will rot in a hole in the ground, the worms will swallow him, bit by bit, and I won’t be able to stop them.”

She looked toward the plain: wild, almost hostile where it had been left unplanted; a gentle nourishing carpet where her son the farmer had sown his crops. Were these fields of wheat and barley, this garden of beans and tomatoes, this peace and contentment, all quite useless now? “Why?” She studied her handsome husband’s face; he too was stooped with grief.

“Adam, why has my flesh murdered my flesh?”

Her sturdy mate’s eyes were swollen. He lifted up his gaze toward the mountain that blocked the horizon, the mountain where Cain had fled. Clouds covered the peak, but the sun shone brightly. The weather was mild, the treetops rustled. Seagulls coming from the north uttered their strange liquid cries. Exhausted by many misfortunes, Adam said wearily, without thinking,

“It’s the will of the Almighty, Eve . . .”

The mother of men sprang to her feet. Shock distorted her dark features. Her voice hissed. “What sort of gibberish is that?”

“It’s the will of Jehovah, Eve. We will have to resign ourselves. He must have his reasons.”

No sooner had he spoken than Adam regretted his words. Eve, eyes popping, grabbed him by the shoulder.

“Repeat that. It’s God’s will. God’s fault? You mean he has reasons for killing a child?”

Adam, the male created in consequence of an inconceivable decision on the part of the Almighty, found his helpmeet terrifying at that moment, as she shouted, “Of course, you must be right. Who else but He would cause such madness. A brother killing his brother. I knew how much Cain loved Abel . . .”

Panic-stricken, the father of men motioned for her to be quiet. Disheveled Eve, with brambles caught in her skirt, expostulated with Heaven.

“Of course. When the older one brought You his offering, the fruits of the earth, You despised his gift…And you exaggerated your pleasuwhen the younger one sacrificed a ewe. And yet You knew that one was proud and the other was vain. . . . And You forced them to fight in Your name, these two boys who adored each other. . . .”

She was choking with rage.

“You are . . . you are . . .”

Adam leaped at her, crushing her lips with his hand. Eve was strong, she took on the heavy chores at harvest time and thought nothing of a three-day trek in search of better pastures. She struggled violently, scratching him while she was at it. Then she elbowed him hard, right in his ribs, so that he nearly fainted with the pain. But he didn’t let go, even when she bit the hand that was trying to smother her. He managed to bring her to her knees and forced her to the ground. She began to moan. With his arms still around her, Adam pressed his lips to her ear and whispered, “Don’t insult Him, darling Eve, mother of my children. He could seek vengeance. He is terrible, as you well know. . . .”

She was able to get the words out.

“Let Him take my life, if he wants to. That no longer frightens me. What’s the use of living, after what He’s done?” And she shuddered and said, “Oh how I hate him!”

Close to tears, Adam spoke again, so softly she ought not to have heard. “Eve, I wasn’t speaking of us, but of our only surviving son. Jehovah can kill him too.” But Eve had heard him. Puzzled, then horrified, she stared at her adored mate. Adam nodded, and reiterated softly, “Yes, He can still attack Cain, who is our only child now. His power is great. He always wins. He’ll devour our boy like a shrimp you pick up by the head. Eve, Eve, pray to God, because He is pitiless and our child is weak.” Eve stood up again, suddenly pacified. She wiped away mucus and tears with her elbow. She straightened her skirts and flashed a faint apologetic smile when she noticed the scratch marks she had left on the face of the first man.

She ruffled Adam’s frizzy hair, as coarse as a tuft of scutch grass, and stifled another sob. Adam wanted to take her in his arms; she broke away and ran to hide in her son’s sheepfold.

Adam spent the rest of the afternoon digging a grave—the first grave! He gave some thought to the correct manner of laying the body in the hole and decided he would slip it in vertically, perhaps because a standing corpse looks less like a rotting carcass. When Abel’s head was no longer visible, Adam the prophet sighed. “You are only the first of a long cohort, my sweet. . . . Is this the purpose for which the dust of the earth was created?”

And he regretted having come into the world.

Waiting for her husband to return home, Eve stretched out on the cool earth. She shut her eyes and at once sank into a deep, coma-like sleep. Her last thoughts before sleeping were for her two children, the living and the dead.

The sun sent its last rays. Droplets formed in the eyes of the world’s first mother, swelled and flowed down the sides of her face. Eve, who knew a great many things unawares (because God, despite everything, had endowed her with part of his foreknowledge), dreamed with boundless sorrow, of the crowd of souls waiting patiently to appear into life. All were created, in one fell swoop, at the same time as her husband’s soul and her own. Confined to a reserve in heaven, they watched for a sign from the Master of the Universe, to come take their place in the human body allotted to them, so that they might endure their portion of suffering on earth.

The sun had all but vanished from the sky. Eve shivered. She tried to rouse herself but lacked the energy to face the new world. With one hand she brushed aside the flowers bending over her. A light breeze touched her face. She reopened her eyes, which were reddened with weeping.

Translation from the French by Suzanne Ruta